Stitch the designs from this dress yourself by machine or hand using the files linked at the end of this post and be sure to share them using the hashtag #CHMRALF!

Stitch the designs from this dress yourself by machine or hand using the files linked at the end of this post and be sure to share them using the hashtag #CHMRALF!

When you come up close and personal with a piece of historical clothing, it’s hard not to wonder what kind of life it had before. In the costume collection at CHM, sometimes the provenance records give a clear picture of a piece’s past, but sometimes they only reveal a tiny portion of it. This 18th-century dress currently on display in our exhibition Dressed in History is one such item, and though we only have documentation on the last 100 years of its life, careful study can reveal so much more!

Front and back views of the robe à la française. CHM, ICHi-179553 and ICHi-179557

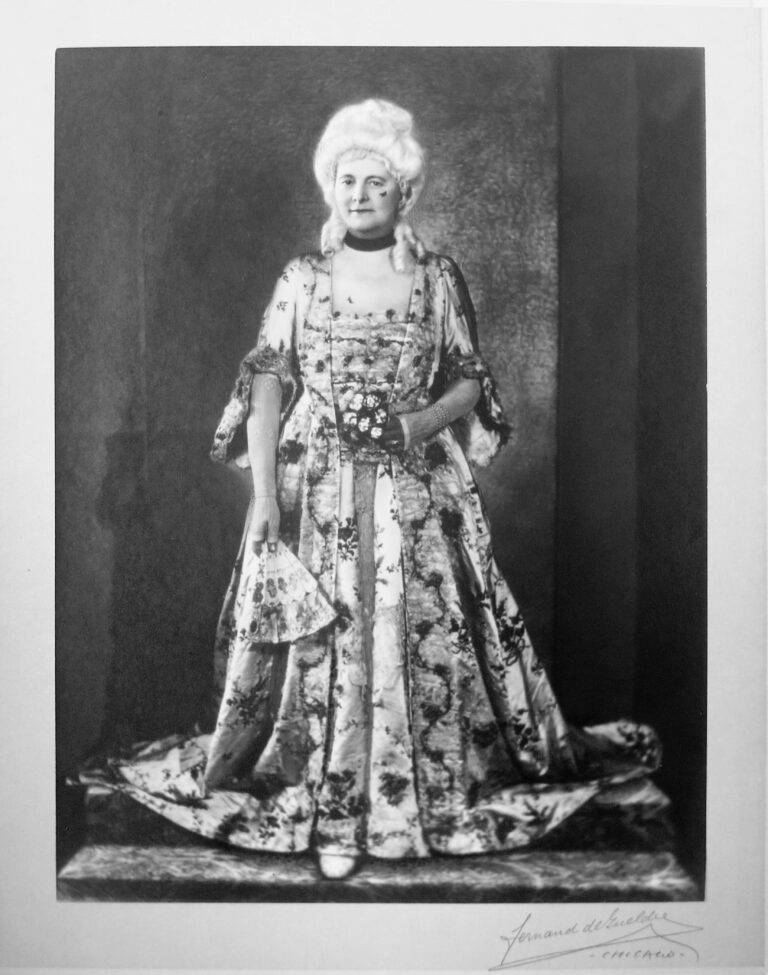

This robe à la française (or RALF, for short), first entered the Museum’s collection in 1920 as part of the Charles F. Gunther Collection and was reported to have belonged to Queen Caroline of the United Kingdom. However, with no evidence to prove the claim, the Museum sold the dress at a rummage sale. Bertha Baur (1861–1967), a wealthy politician, businesswoman, and socialite, bought it in 1926 for $150 and wore it to various fancy-dress balls and parties. She modified the dress by adding a wide elastic waistband to the underskirt. In 2016, her granddaughter Romia Bull donated the gown to the Museum.

Bertha Baur in her robe à la française at the Art Ball, Chicago, c. 1927. CHM, ICHi-183726

So, what can we learn about this dress’s life before it came to Chicago? We brought in embroidery expert and historical costuming superstar, Dr. Christine Millar (known as @Sewstine online) to study and digitize the embroidery on this dress for anyone to use. Research and insights analyst Marissa Croft sat down with her to find out more about what she learned after studying this gown.

Dr. Christine Millar studying the robe à la française with mount maker Michael Hall.

Marissa: What is special about this particular dress?

Christine: I can’t emphasize enough that this is a very unique dress, because there are very few surviving examples of fully embroidered 18th-century dresses. Robes à la française with designs are usually made of brocade fabric, which is woven using special looms. The embroidery on this dress, on the other hand, is done by hand on a very fine silk material. First, the material would be stretched over a hoop, then the design would be penciled onto the fabric, before finally being sent to a workshop to then be meticulously stitched out by a team of embroiderers.

The fabric used in the dress is 28 inches wide and there are about 20 yards of hand-stitched fabric in the dress. This amount of embroidery would have been a true status symbol. It likely took months to stitch out. In all my years of looking online and visiting museums, this is my first time seeing a gown where the fabric was fully embroidered and then stitched together!

M: Can you tell us a little bit about the materials used in this dress?

C: The stitching was done with chenille thread, which looks like pipe cleaner without the wire. It’s stitched on beautifully woven silk satin, and the weave is so tight, there’s really no comparable fabric like it being made today. The dress also has yards and yards of handmade 18th-century fly-fringe or passementerie trim on it, which are made from the same chenille thread as the embroidery, so we can assume it was probably created around the same time as the fabric was stitched.

Detail shot of the passementerie and lace on the dress. [Image by Marissa Croft]

M: What do you like most about embroidery?

C: You’re essentially painting with threads, there’s so much more shading and depth to the designs so the overall effect on the fabric is so different from brocade, more 3-dimensional. I also love that with this embroidery pattern, all the bouquets of flowers are slightly different designs, and that really pulls at my heartstrings because they’re all done by hand, by a human! When I digitize these hand-created motifs, I like to also try to capture that organic nature.

M: How did you first get into embroidery and historical costume?

C: I started as a cosplayer, but I’ve been making costumes since I was a kid. At NYU in undergrad, my favorite clothing pieces I came across were always ones from history, because I was entranced by the level of detail they had. I love to try and copy museum pieces, because it adds another layer of challenge and allows me to be much more detailed.

As for embroidery, I’ve always been someone who loved illustration, so I’m drawn to embroidery’s illustration-like properties. However, hand embroidery can take such a long time to do, so with my first paycheck as a doctor I bought an embroidery machine and the software. It’s so satisfying to draw something on the computer and then it comes out painted in thread on a beautiful fabric a short time later!

What did your digitization process look like for this design?

This design took about 12 hours total. First, I used my phone to get a perfectly flat image from above, with a ruler for scale. I then brought the images onto my computer and started digitizing it one color at a time, figuring out which direction the stitches would need to go in. Then, I ran tests of the designs, going color by color.

Even though the stitching on a machine may go faster, switching colors to get the layers of the design right can take more time vs stitching it out by hand, which was how these flowers were originally made. There are about 60 color changes in this design!

Disclaimer: These designs are for personal, non-commercial use only. These designs have been digitized in a public-private partnership. As part of this partnership, the partners have agreed to limit commercial uses of this digital representation of the embroidery designs by third parties. You can, without permission, copy, modify, distribute, display, or otherwise use these designs for noncommercial purposes.