Each fall, people in Latine communities around the world remember their deceased loved ones during Día de los Muertos. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about how contemporary Day of the Dead celebrations mirror the hybridization and mingling of Indigenous and Catholic roots through Spanish colonization of Latin America.

Ofrenda installation at NMMA by Alejandro García Nelo, “54,950 heartbeats: A tribute to the victims of the earthquakes in Turkiye, Syria and Morocco,” 2023. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is strongly associated with Mexican communities but today is celebrated throughout Latin America and globally by the Latine diaspora.

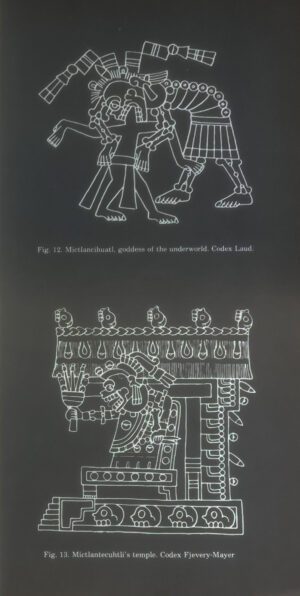

Illustrations depicting Mictēcacihuātl from Exhibition catalogue for NMMA’s (then the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum) Día de los Muertos exhibition, p. 9, CHM Collection, GT4995 A4D52 1991

It is a holiday rooted in Indigenous tradition that has evolved through the centuries. The Aztec Empire celebrated the Lady of the Dead or Queen of the Underworld, Mictēcacihuātl, as an Indigenous spiritual tradition. Mictēcacihuātl is said to protect bones of the dead so they may be returned and used in the land of the living. Spanish conquistadores observed this tradition and fused Aztec traditions with the Catholic holidays of All Saints Day and All Souls Day as a tool for colonialism and forced conversions. In Spain, Catholic celebrations of All Saints Days and All Souls Days were celebrated by decorating family graves and sharing food graveside as way of remembering and communing with deceased loved ones. Contemporary Day of the Dead celebrations mirror the hybridization and mingling of these Indigenous and Catholic roots through Spanish colonization of Latin America.

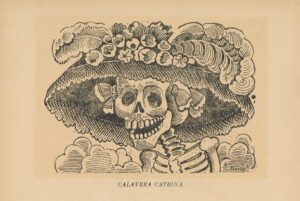

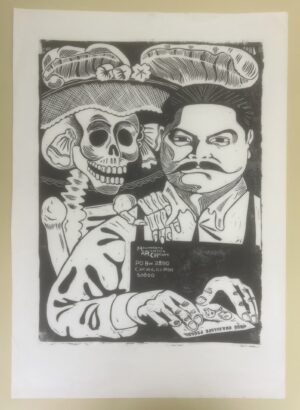

(L) Calavera de la Catrina, from the portfolio of 36 Grabados: José Guadalupe Posada, published by Arsacio Vanegas, Mexico City, c. 1910. Public Domain. (R) José Guadalupe Posada print by artist Carlos A. Cortéz Koyokuikatl, showing Posada’s La Catrina, 1981. CHM, Broadsides collection.

In the visual language of today, Mictēcacihuātl typically takes the form of La Catrina, a skeletal female figure wearing a European-style woman’s hat. This is credited to the influence of Chicago activist-artist Carlos Cortéz Koyokuikatl’s reuse of a popular image created by Mexican engraver and printmaker José Guadalupe Posada.

View of the Celebrando Comunidad mural by Liz Reyes in Little Village at 26th Street and Lawndale Avenue, October 18, 2019. CHM, STM-087170528, James Foster/Chicago Sun-Times

(L) NMMA installation: Familia Jiménez, Leo Parga, Araceli Muñoz, Mireya Bautista and Héctor Martínez, Öfrenda for Guadalupe Jiménez (1957–2022), 2023. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman. (R) Ofrenda in Dunkin Donuts in Pilsen, 2023. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Another of the most recognizable elements of Día de los Muertos is the ofrenda, or altar. Seen in homes, along streets, on sidewalks, in stores, and in cemeteries, ofrendas are literal offerings to the spirits of deceased loved ones. They often feature photographs as well as favorite items of those who have passed on, including foods like pan de muerto, water or other drinks, and favorite toys or activities. Ofrendas are also usually decorated with cempaxochitl/cempasúchil, or marigolds, which symbolize life’s fragility. Their bright orange color and distinct smell act as guides for bringing spirits back for the time of celebration.

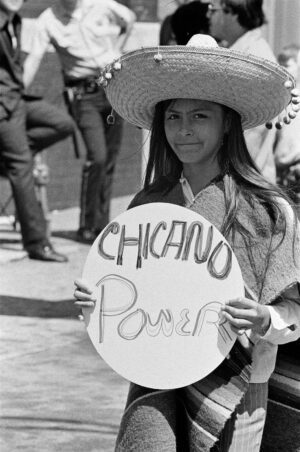

(L) Person holding a sign that reads “Chicano Power,” July 19, 1971. CHM, ST-60004929-0031, Chicago Sun-Times collection. (R) Mural, July 19, 1971. CHM, ST-60004929-0145, Chicago Sun-Times collection

While Día de los Muertos had been celebrated in Mexico for centuries, its arrival to the United States coincided with Mexican immigration during the second half of the 19th century. For decades, the tradition was kept by families through religious masses and visits to family graves, but gatherings remained small and more private. This began changing through the 1960s and 1970s with the rise of the Xicano/Chicano movement. El Movimiento pushed against structural racism through centering bold expressions of Mexican and Latino identity in the public sphere. Activist efforts included political actions, student walk outs, and protests but also included arts such as visual and poster art, literature, music, and murals. Chicano activists began marking Día de los Muertos boldly in community, using it as a way to educate the broader public about Mexicanidad and carefully distinguishing it from Halloween.

Exhibition catalogue for NMMA’s (then the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum) Día de los Muertos exhibition, Cover and frontispiece, CHM Collection, GT4995 A4D52 1991

As this exhibition catalogue demonstrates, the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) has played a key role in amplifying Day of the Dead in Chicago. Since 1987, they have held an annual display of commissioned ofrendas, each year shifting focus on a different theme, but all centered in preserving this ancient tradition while bringing new relevance. Additionally, their Día de los Muertos Xicágo gathering features dozens of ofrendas made by community members as well as art activations and live music.

(L) Carlos Totolero and Helen Valdez, two of the cofounders of the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum (now NMMA), February 13, 1992. ST-19040944-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. (R) Students visiting the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum (now NMMA), February 13, 1992. ST-19040944-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

NMMA was founded in 1982 by a group of six educators. Originally called the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, they wanted to create an organization that centered Chicago’s Mexican community through accessible, social-justice oriented educational and cultural programming. They first opened to the public in 1987 in Chicago’s West Side Pilsen neighborhood, repurposing the Harrison Park boat house. In 2001, they expanded into a 48,000 square foot facility and officially changed their name in 2006 to NMMA to better reflect their expanded mission. Recognizing Mexican identity is sin fronteras, or without borders, the NMMA continues today, welcoming over 150,000 guests annually.