Jean Boulet’s first helicopter flight was almost his last.

It was September 21, 1947, and the 26-year-old Boulet was at the Camden, New Jersey, headquarters of Helicopter Air Transport, the world’s first commercial helicopter operator. He had earned an engineering degree from the École Polytechnique in Paris and had been a member of the French air force during World War II. After the liberation of France, the air force sent Boulet to the United States for fighter pilot training. He returned to France in 1946, but the war had ended and “there were many pilots and not enough planes,” Boulet told the author in an interview in the 1980s. “I didn’t think there was too much of a future for someone who had not flown during the war, so I left the air force.”

Despite the glut of former military pilots on the market and his relative lack of experience in the air, Boulet remained determined to make flying his career. “I started looking for civilian flying jobs and received a proposal from SNCASE [Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautique du Sud-Est] which was just beginning to develop helicopters,” he said. “I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to do the job because I couldn’t fly helicopters, but they said nobody knew anything about flying them.”

SNCASE sent Boulet to Helicopter Air Transport, which also ran a training program for pilots, and that’s how he ended up in New Jersey and in the copilot seat of a Sikorsky S-51.

“The first day I saw a helicopter, I had my first ride and my first accident,” Boulet recalled. “The instructor did not have a lot of experience, and at the end of the flight the helicopter started to rock back and forth very quickly. I thought he was doing a nice demonstration of the helicopter’s agility, but he had really lost control. We crashed, rolled over, the blades were broken, the aircraft was a mess, but luckily, we were only shaken up a little. This experience gave me a mistrust of this very strange flying machine.”

(Robert Doisneau/Getty Images)

Despite this rather dramatic and nearly catastrophic introduction to the helicopter, Boulet would soon become the primary helicopter test pilot for SNCASE, which later became Sud Aviation and then the helicopter division of Aérospatiale. As these companies grew into one of the world’s leading helicopter manufacturers, Boulet was at the controls for test flights of the SE-3101, Alouette I, II and III, Frelon, Super Frelon, Lama and Puma helicopters. He helped define the role of helicopter test pilots in the development of new aircraft. “We suggest and request modifications and we decide the way a helicopter must be flown,” he said. “We request things such as an increase in power, which we did for the Alouette II.”

Boulet also set the world’s record for helicopter altitude three times. His third record-setting altitude flight almost ended in disaster after the engine of his Lama flamed out during a descent through a thick layer of clouds. As he always did, Boulet managed to find a way to survive.

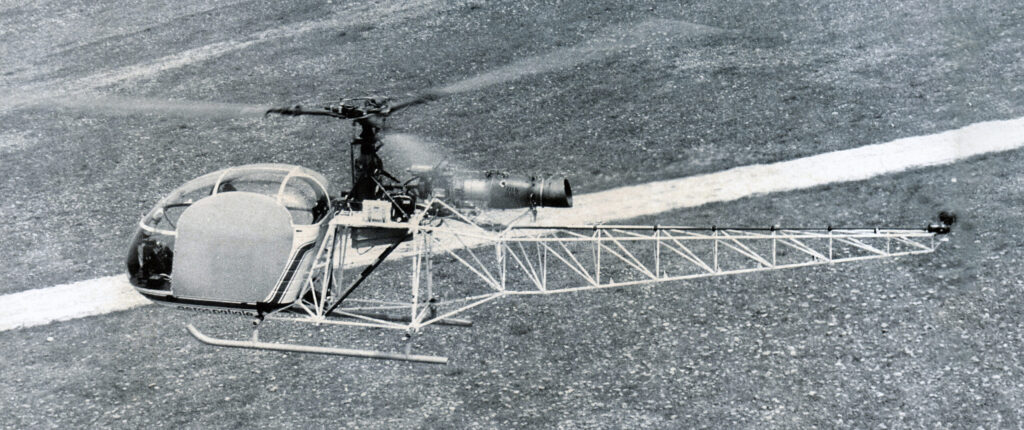

After the crash landing in New Jersey, Boulet was able to fly 10 hours in another Helicopter Air Transport helicopter before the company went bankrupt and ceased operations. He completed his helicopter pilot training in Scotland and returned to France and SNCASE, which was ready to test fly its first helicopter, the SE-3101, in June 1948. The SE-3101 was an experimental helicopter designed by German aviation pioneer Henrich Focke of Focke-Wulf fame. An updated version of the Focke-Achgelis Fa 223, it had twin tail rotors, an uncovered fuselage and was powered by an 85-horsepower Mathis engine. After months of tie-down tests, the helicopter was ready for its first flight.

Another pilot, who had experience with autogiros, was going to make the first test flight. He was a bit heavier than Boulet and the underpowered aircraft was unable to lift off the ground. “So, the manager told me to try because I was lighter,” Boulet said. “I was young and thin and was able to take off and hold it off the ground.” This was “the first helicopter to be flown in France after the end of the war,” said Charles Marchetti in Vertical Flight: The Age of the Helicopter, a book published by the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in 1984. Marchetti was a chief engineer and the Aérospatiale helicopter division general manager.

The SE-3101 flew a total of about 20 hours over the next two years but did not go into production due to several stability and control problems. It was able to achieve “satisfactory” forward flight without too much instability or vibration, according to Marchetti, but “during hovering and approach or forward flight near the ground the instability of the aircraft became obvious.”

(Keystone Press/Alamy)

The company’s first production helicopter was the SE-3130 Alouette II, which was also the first production helicopter with a gas-turbine engine instead of the more conventional piston-driven engine. The first flight took place on March 12, 1955, with Boulet at the controls. “[W]e had a few problems to solve, but we were able to solve them by working very hard because we knew we had to catch up with the American industry which had started production in 1944,” he said. Eventually the company manufactured more than 1,300 SE-3130s.

Boulet was SNCASE’s only test pilot in 1955, which was problematic. “The company said you cannot be the only one because if you are ill, we cannot fly,” Boulet said. “So, we engaged more pilots, three or four in 1956 and 1957.” The number of test pilots grew over the next few decades. “When I was chief test pilot, I always had control and would not do things I did not think were safe,” Boulet said. “And when the other pilots flew, I always signed the flight order. I only lost one pilot. He was doing a demo flight in Germany and ran into a cable. It was the only bad accident we had. We had some crashes, but not any other bad crashes.”

Boulet first attempted to break the helicopter altitude record on June 6, 1955, in the Alouette II, just three months after the aircraft’s first flight. The existing record was 24,524 feet, set by U.S. Army warrant officer Billy Wester in a Sikorsky S-59.

The higher a helicopter ascends into the thin air at high altitudes, the more difficult it becomes for the engine to maintain power and the rotor blades to maintain lift. Yet Boulet said the flight, during which he reached a record 26,932 feet, “was not very difficult.” This is an example of his modesty, as the flight was, in fact, quite difficult indeed.

He took off from the Buc airfield, about 10 miles southwest of Paris. “I just had to apply the pitch and climb,” he said. “But there was a problem with cockpit icing and I couldn’t see too well. Then, when I started to descend, I had a flame-out and couldn’t restart the engine.” Boulet was forced to autorotate, a technique where the pilot disengages the main rotor from the engine so the blades can be rotated by aerodynamic forces only, without any mechanical assistance. Autorotation will slow a descent but won’t stop it. “There was a strong wind that took me very far from the field I took off from, but I was able to land.” Boulet’s record was broken in December 1957 when U.S. Army captain James Bowman reached 30,335 feet in a Cessna YH-41 Seneca helicopter.

(Airbus)

On June 13, 1958, Boulet began heading skyward in another Alouette II, determined to regain the helicopter altitude record for Sud Aviation and France. He climbed quickly when “suddenly I heard a loud bang and the engine stopped,” he said. Once again, he had to autorotate. “When I landed, we discovered that the casing of the engine had broken completely in two.” Despite the broken engine, Boulet had reached 36,027 feet and reclaimed the altitude record.

In the meantime, SNCASE merged with SNCASO (Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautique du Sud-Ouest) to form Sud Aviation, and Marchetti began designing the larger, seven-seat Alouette III. The helicopter made its first flight on February 28, 1959. Boulet was at the controls and flight engineer Robert Malus was also aboard. Marchetti reported that the new helicopter flew beautifully and that Boulet managed to land a fully loaded Alouette III on top of France’s Mont Blanc, an altitude of 15,777 feet. “In November 1960, on the occasion of a presentation in India, he landed with a passenger and 250 kilograms (551 pounds) of cargo in the Himalayas at an altitude of 6,004 meters (19,698 feet). At that time, this was an unprecedented feat.”

Sud Aviation’s next aircraft was the Frelon, which was the forerunner of the more successful SE321 Super Frelon. A long list of problems was discovered in the early test flights of the Frelon, Boulet reported. “This helicopter had three engines which was something very new for us and we had a lot of problems, with incidents on almost every test flight. Once we had a severe instability with the helicopter. I was just about to tell the crew to jump out, but then I was able to gain control at the very last minute.”

On another test flight, problems with faulty servocontrols almost caused a crash. “It was not possible to hold the stick because it was moving completely to the left, and I could not pull it back, no matter how hard I tried,” Boulet said. “Finally, with the help of my copilot, I was able to pull the stick back and gain control. This was not a very fun test program, and the crew was always tense during test flights.”

Test flights for the Super Frelon began in December 1962 and were a lot more successful than those for the Frelon. With Boulet at the controls, the Super Frelon set a new speed record for helicopters of 350 kilometers an hour (217.5 miles per hour).

(Airbus)

To meet the French army’s new requirement for a medium-sized, all-weather helicopter, Sud Aviation began developing what would become the SA 330 Puma. The prototype made its first flight on April 15, 1965. As usual, Boulet was flying and, of course, there were problems, as there are in the initial test flights of almost every prototype aircraft. There were a lot of vibrations “that made it very unpleasant for the pilot and crew,” Boulet said. It didn’t really make it harder to fly, but it was difficult to see the instruments because of all the shaking.”

Marchetti and his team solved the shaking problem by developing a suspension system that isolated the gearbox from the rest of the aircraft. It was called the “barbeque system” because the structure resembled a barbeque grill. Sud Aviation ended up manufacturing about 685 Puma helicopters.

In 1970 Sud-Aviation became Aérospatiale and in quick succession designed three new, single-turbine helicopters: the Gazelle, Écureuil and Dauphin. The Gazelle had two unique features: fiberglass rotor blades and the Fenestron design in which the anti-torque tail rotor was surrounded by a circle of material instead of being completely exposed. Boulet especially appreciated the Fenestron, which he referred to as “the fan-in-fin tail rotor.” “I had a bad experience at the beginning of the Alouette II test program,” he said. “I was at the controls with the aircraft on the ground, and a man who was not noticed by the mechanics walked head-first into the tail rotor. It was horrible and there was blood everywhere and pieces everywhere. I was traumatized by this and lived in fear that it could happen again. Because of this, I loved the Fenestron and worked very hard to make it successful.”

Boulet was not as taken with the fiberglass rotor blades that had replaced the traditional metal blades, at least initially. “At high speed we had a lot of flutter, and this, of course, meant a lot of vibration,” he said of the early test flights with the composite blades. “This [vibration] was so bad that I thought the helicopter was going to break into pieces. The stick was moving all over the cockpit, but happily, after a few seconds, I was able to recover with the help of the copilot.”

Aérospatiale’s SA 315B Lama was a redesigned and more powerful version of the Alouette II that was intended to fly at high altitudes and in hot temperatures for the Indian army. It was first manufactured in 1971 and Boulet decided this was the perfect helicopter in which to set a new altitude record. To make that possible, it was necessary to lighten the aircraft by removing all possible instruments, taking out the passenger seats and replacing the standard fuel tank with a smaller one. Engineers modified the turbine Turbomeca engine to increase power by about 6 percent. After Boulet started the engine, mechanics removed the battery and starter motor to further lighten the aircraft.

Boulet and the Lama leaped into the air on June 21, 1972, from an airfield near Marseille. Trouble started almost immediately. “During the climb, there were some clouds, but I was able to climb through a hole in them,” he said. “But all the time I was worried about my descent.”

(Airbus)

Boulet was able to reach the stunning altitude of 40,820 feet and smash the previous record of 36,027 feet he had set in 1958. However, his worries on the way up proved prescient on the way down when Boulet couldn’t find the hole in the clouds for his descent. “My cockpit was completely frozen, and visibility was very bad. And also, there was some mist on the ground, which made it very hard to see the ground and tell how high up I was.”

As if these weren’t enough problems, as he began to descend through the clouds, his engine failed. Without the generator and battery, which had been removed, he had no way to restart the engine. This meant Boulet would have to perform the world’s highest and most dangerous autorotation, without the help of the horizon indicator and compass, which had also been removed. “So, I had to go through 13,000 feet of clouds without instruments,” Boulet said. “The only way for me not to go upside down was to watch for the brightness of the sun. I could barely see where the sun was by looking for the bright spot in the clouds, and I tried to keep this spot above me.”

Using every bit of the experience he had gained over the years, Boulet managed to keep his helicopter upright. After he broke through the clouds, the warmer air below melted the ice from his cockpit and windshield so Boulet was finally able to see where he and the Lama were going. He landed safely after a descent of about 25 minutes.

This was Boulet’s third and final helicopter altitude record, and it has yet to be broken.

Boulet remained Aérospatiale’s chief test pilot until he retired in 1975, ending one of the most illustrious careers of any helicopter or fixed-wing test pilot. “The rest of us were like members of the orchestra, which Boulet was the star soloist who could take your breath away,” said Claude Picard, a helicopter pilot and a member of Aérospatiale’s public relations department.

“I loved my job; it was the only thing I wanted to be doing, and I did everything possible to reduce the risks,” Boulet said, adding that there were times when he was frightened. “I remember a few times when I was scared, especially in the days of the Frelon. I put on some warm clothes because when you are scared, you are shivering.” There were also a few perks available to the chief test pilot that helped compensate for the occasional terror. Boulet said that he often flew a helicopter he was testing to his nearby home to have lunch with his wife. And, from time to time, he was able to “borrow” a helicopter for a weekend of skiing. “This was because in France at that time we had very liberal civil aviation regulations and you could go anywhere provided you had permission of the owner,” he said.

In the years after he retired, Boulet kept busy skiing, lecturing and writing. He also wrote History of the Helicopter as Told by Its Pioneers 1907-1956, which he published in 1984. Boulet died on February 13, 2011. He was 90.